The Miracle of Providence Spring

By Richard Salzberg / ©2017

The grievous conflict of the Civil War remains the most convulsive, destructive, and still compelling chapter in the nation’s history. By 1864 the conflict was in its third year, and the North’s strategies, in combination with its resources and resolve, had begun to finally subdue the South. Union victories on the battlefield had grown more numerous, and the war of attrition as envisioned by Lincoln, along with the Anaconda Plan as originally conceived by Winfield Scott, were proving brutally successful. An extension of the attritional war included the decision by Lincoln and General Grant to put an end to what had been large general exchanges of prisoners-of-war between the two sides. This action succeeded in further eroding the manpower which had become the Confederacy’s last natural resource, while it also resulted in tens of thousands of soldiers from both armies languishing hopelessly in what became little more than death camps in both North and South.

Despite the unconscionable conditions which existed in the prison camps of both sides, the Confederate prison at Andersonville, Georgia has come to symbolize the worst of all of the camps; and, by extension, it serves to represent the very worst aspects of America’s vicious war between countrymen and brothers.

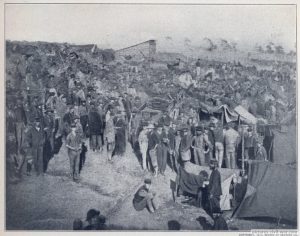

Andersonville is about 110 miles south of Atlanta. From its inception as a prison camp in February of 1864 until the war’s end in April of 1865, a total of 45,000 Union prisoners-of-war passed through its gates. As many as 32,000 men were interned there at one time. In a vast outdoor pen of about 26 acres, surrounded by a 15 foot-high stockade made of upright rough-hewn pine logs driven straight into the ground, those poor souls within its confines were provided with little food, and no shelter whatsoever. The winter months were cold and relentless, and in summer the scorching sun and heat were deadly for the already weakened captives.

Men who arrived without tents or blankets, or any crude utensil needed for the digging of hovels into the hard red Georgia clay died unattended on the open ground; and from the very first, prisoners died by the hundreds.

Untreated wounds and disease, the incessant hunger and thirst, as well as a mortal despair, all combined to leave the tragic legacy of a death toll of more than 13,000 men. What had been the sleepy railroad town of Andersonville became a name synonymous with a veritable hell on earth, a nightmare of unimaginable dimension, unreal and impossible to ever fully describe even by those who were there.

Andersonville

By 1864 food was scarce throughout the South, and scarcer still for the ill-fated Union prisoners. But, as is ever the case in the history of such human misery, it was the lack of water and the torture of continuous thirst which became most destructive to body and mind. At Andersonville there simply was not enough water for so many men. In fact, because of poor planning and design, and the influx of such unexpected numbers, there was no clean water at all.

Stockade Creek was the name for the pitiful stream which ran through the lower third of the prison ground. With the exception of several small wells dug by prisoners, it was Andersonville’s only source of water; but before it ever entered the prison it was befouled by the cooking and contamination from the adjacent Confederate guards’ camp outside the stockade. The low banks and areas all around Stockade Creek became a vast and fetid morass in a very short time, for it was also used as the prison’s open latrine.

With no officers among the unfortunates at Andersonville, there was no formal leadership or organization. The basics of survival became the responsibility of the individual prisoner, and the sole occupation of each man. Beyond the deathly sick and the wounded, those without any sort of personal purpose or direction were inevitably the first to die. Within such an incubator for the worst sort of human suffering and misery, the actions of the individuals at Andersonville ranged from the extraordinary to the unforgivable.

While some prisoners became part of the feared gangs which organized to exploit and brutally prey upon their comrades, such as the notorious “Andersonville Raiders,” other men dedicated themselves to providing as much assistance and comfort as possible to the infirm and dying. Also, as the long months passed within the camp, religious activities became an important part of many of the prisoners’ lives. Interest in prayer meetings and growing attendance enabled them to be held each night in different parts of the camp, and preachers of all sorts emerged from the desperate ranks to hold services and to minister to the wavering hopes and spiritual needs of the forlorn men. An Andersonville Sunday School was even established; and even as the camp’s horrid conditions became worse, the numbers of the faithful grew.

June and July of 1864 brought weeks of searing heat, and the number of dead steadily grew. Loaded in crude carts and carried outside the stockade to what was known as the Dead House, they awaited a primitive mass burial in the long, shallow trenches dug by their comrades. Such was the particular hell of Andersonville that, although surrounded by tall Georgia pines, the prisoners had no wood to boil the filthy water; and in the midst of what had once been rich farmland, they had no food. And men within the stockade were dying from thirst only yards from the clear, free-flowing waters of Sweetwater Creek which ran just outside of the south wall of the prison.

But in early August the rains came.

The blessed relief began as light showers which came down and rinsed the mass of 30,000 prisoners as they lie about the seared open acreage. Then, as the rain grew stronger, the men looked skyward and opened their parched mouths. Soon, all those who could began to hold up battered canteens and tin cups, and any other vessels they could find to hold the clean, precious rainwater. The downpour soon became a torrent which soon turned the prison’s 26 acres into a vast quagmire. As the heavy rains continued, Stockade Creek rose higher, overflowing its banks and carrying away large quantities of the camp’s accumulated filth and mire with its strong new current.

Survivors testified after the war that the stream rose five feet in one hour. Eventually the surging water carried away portions of the east and west stockade walls. Although the Confederates hurried to arms in anticipation of the threat of a mass escape, the prisoners were simply too weak to much more than avoid the rushing water, and to revel in the relief from the torments of thirst and the burning sun.

After five days of intermittent rain, on August 13, the great cloud appeared. Distinctive for its tremendous size and sharply defined shape, it was said to be like a giant mountain in the sky, its color like that of blued gun metal. Approaching from the east, the cloud moved slowly westward until it was directly over the camp. As thousands of men watched with a growing sense of awe, it seemed to stop and hover directly above the bough-covered Dead House, before moving slowly towards the North Gate.

Even the nervous guards were compelled to stare in wonder as the cloud loomed, over the prison, still and powerful. By this time most of the camp’s crude shelters had been washed away by the rains, and the prisoners had been soaked to skin for days. Now, as the emaciated men stood staring heavenward, for the first time at Andersonville Prison there was complete silence. Even the endless drone of misery from the sick and dying became muted, then seemed to disappear. As the cries of suffering quieted, a soft rain could be heard falling gently upon earth and man.

Suddenly, there came a thunderous, deafening roar. From men who knew the sound all too well, it was said to be like the explosion of a thousand cannon. It was so powerful that the weaker men standing near the west wall were thrown to the ground. Then, from the heart of the deep blue cloud, came a great, blinding flash – followed nearly immediately by searing bolt of blinding white lightening. It too exploded from the sky, violently striking the earth just within the stockade at a notorious point known as the Dead Line, beyond which no prisoner could pass without being shot. At the place where the fiery lightening struck there was another tremendous explosion, and a stunning eruption of earth and steam filled the air. Instantly, torrents of fresh water gushed from the blasted, broken ground, pouring forth and coursing into the prison. This awesome water was cool and clean, and its flow was to become a permanent thing.

The thunderous lightening had found the highest point of an underground stream, and the name of Providence Spring emerged nearly as quickly as the waters came forth to the relief of the thousands.

Providence Spring at Andersonville today

On that same day the rains stopped, and the stockade walls were soon repaired. No attempts at mass escape were ever made, nor any effort made for the prisoners’ liberation by Union forces, even when Sherman’s army was within 20 miles of Andersonville on their “March to the Sea.” The imprisonment and harsh conditions for thousands of Federals continued through another long winter, and until the war’s end in April of 1865; but throughout that entire time the miracle waters of Providence Spring continued to flow at the rate of about 10 gallons per minute. All who were there knew how rare a thing it was, but among the religious and newly religious in the camp, there was the special knowledge that the prayers of men in the most desperate sort of need had been answered. The awareness and belief that plaintive supplication could be heeded from even such a forsaken and miserable place as Andersonville was infinitely gratifying.

Shortly after war’s end, Clara Barton and a former prisoner by the name of Dorence Atwater went to Andersonville as leaders of a dedicated group whose mission was to exhume, identify, and then properly rebury the scores of Union dead from the mass graves. Atwater, known as “the Clerk of the Dead,” had worked in the Dead House and somehow managed to record and secrete thousands of names. Incredibly, all but 400 of the 13,000 men who died there were successfully identified by this inspired effort. In the midst of such gruesome work in the sweltering heat of a burning July, those courageous and inspired humanitarians joined the prisoners who had gone before them whose bitter thirst had been quenched by the cooling, mysterious waters of Providence Spring.

Today, Andersonville is a very quiet place. Still a part of the rural Georgia countryside, it is a National Historic Site administered by the Park Service. There is a modern Visitors Center with affecting displays that communicate the tragic history of the place effectively. There is also the Andersonville National Cemetery. Originally dedicated by Clara Barton’s group in 1865, the cemetery continues to provide a final resting place for American veterans today.

A visitor to Andersonville today can tour the 515-acre expanse by foot or by car. Beyond the modernities, once close to the impressive site of the actual stockade, one rather surprisingly becomes aware of a pervasive sense of rare quietude, as a curious sort of peacefulness seems to emanate from the place. It is as if the fiery heat of a great mythological furnace had somehow burned away all of the worldly dross from this one sacred point on earth, leaving an area of serene tranquility. When asked about this impression, a receptive Park Ranger acknowledged that even in summer there comes an unexpected, cooling breeze from the west; and during the coldest of Georgia winters, the area within the lines of the stockade always seems to be a bit warmer than anywhere else.

Walking the now cleared, rolling land where so many men had been left to their fates and struggled to survive in such deadly misery, one can still see traces of half-dug wells and hovels scratched nearly by hand in the hard red Georgia clay, and the remnants of hopeless efforts at escape tunnels. There are also the more recent covered trenches of the archeologists who have discovered large pieces of the stockade’s original wooden palisades beneath the earth; and since 1987 the National Park Service has reconstructed portions of the stockade to “enhance visitor understanding of the prison and prison conditions.” And along the lower portion of the boundary of the west wall, just below the North Gate, there is an impressive shrine made of rough-hewn granite stones surrounding a fountain. With an appearance like a small chapel, it was built and dedicated in 1907 by Union veterans and survivors of Andersonville. The memorial rests at the mouth of Providence Spring, and the clear water still flows at the rate of about 10 gallons per minute. The water there is always cool, and is said to be especially invigorating.

The symbols of the history of our relatively young nation are continually threatened by unconscionable development and ignorance, but meaningful places possessed of great spiritual resonance still exist throughout the land. Of such sites, Andersonville is easily among the most prominent. For those who are aware of it, there is a responsibility to learn from the entire experience, to share the saga with others, and to urge a visit.

To know the story of the Miracle of Providence Spring is to understand that there remain accessible, powerful mysteries and rarified spaces where rare things have occurred, and where they continue to resonate on what can only be described as hallowed ground – at least at a place called Andersonville.