Wars in the East

By Richard Salzberg © 2012

_____________________________________________

“All you have to do is think of the names,” he was saying.

“What names – ?”

“The names of places in the East that might sound strange the first time you hear them, then you sort of just take them for granted. Then you might think about them a minute, and you realize they make no sense at all. Rivers, too.” He nodded as if there was one nearby. “I mean, what does ‘Mississippi’ mean?”

“All Indian names. . . how about, like. . . Ohio?”

“Sure. Even Kentucky. Indian names. In the East. States, cities, and small towns, everywhere. Think about it. . .”

“Is that some of your. . . ‘toponymy’ – is that how you say it?”

“Yeah, I guess that’s what it is.”

¶ ¶ ¶ ¶

When he was shot and killed in front of his young sons in 1786 by an Indian in hiding as he cleared land for his new farm in far western Virginia (now Kentucky), Abraham Lincoln – Revolutionary War veteran, pioneer, and grandfather and namesake of the future president – became a tragic part of the historical circumstances known as the Colonial Wars. His death and its context provide important material for consideration.

No one is certain yet which ancient peoples were displaced in North America by the Native Americans first encountered by Europeans in the New World, although it is likely that their tribal mix was as myriad as that of their usurpers. But there is no doubt that from their very earliest encounters, the relationship between the Indians (used here simply as an easier term) and Europeans – and subsequently, colonial “Americans” – was characterized by mistrust, violence, and war.

No one is certain yet which ancient peoples were displaced in North America by the Native Americans first encountered by Europeans in the New World, although it is likely that their tribal mix was as myriad as that of their usurpers. But there is no doubt that from their very earliest encounters, the relationship between the Indians (used here simply as an easier term) and Europeans – and subsequently, colonial “Americans” – was characterized by mistrust, violence, and war.

In his Editor’s Preface for Howard H. Peckham’s “The Colonial Wars 1689-1762” (1964), referring to lands east of the Mississippi, as are we, Daniel J. Boorstin writes that America’s colonial wars “. . . are among the most dramatic and least understood in our history. . . From a European capital the backwoods battles might have seemed only episodes in a continuing, far-flung struggle for empire. But the American remained at the scene of battle. Long after the bands of European soldiers had dissolved or returned across the Atlantic, he reaped a deadly harvest.”

What needs to be remembered is that the term “American” should include all who lived here. The Indian Wars which claimed the life of the elder Abraham Lincoln and countless thousands of others could be described as a series of internecine conflicts, characterized by a cross-cultural familiarity and a level of ferocity on both sides which even today is hard to imagine. These centuries-long wars were also responsible for a very early and popular genre of American literature now generally forgotten – first-hand accounts of their experiences by former captives of the Indians.

In the book “Scalps and Tomahawks: Narratives of Indian Captivity” (1961), editor Frederick Drimmer states: “When serious trouble erupted between the white man and the Indian, its cause could usually be summed up in a single word: land. The number of settlers was always increasing and they kept pressing westward, hungry for more and better land. Frequently the Indian’s best hunting grounds were taken from him by treaties that he signed but did not understand, or frontiersmen moved in on territory without his consent.”

Less considered are any periods and examples of relatively peaceful interaction and practical respect between neighboring communities. However, once set, the fires of greed and revenge spurred ravages now only dimly remembered, if at all.

The national character of the settlers, the newest “Americans,” was just emerging, while that of the Indians had been evolving for many centuries and was characterized by venerated traditions and a complexity borne of the sheer number of the tribes and their long histories. If the Indian nations were to be removed from their own lands, it would not be without resistance.

• In 1755, James Smith was an 18-year old road builder for the army of General Edward Braddock, the ill-fated commander-in-chief of all British forces in North America. Captured by Indians allied with the French in the wilderness near what today is Bedford, Pennsylvania, Smith was very fortunate to be spared and actually adopted into the Caughnawagas, a tribe related to the Mohawks. In his “An Account of the Remarkable Occurrences in the Life and Travels of Col. James Smith” (1799), he wrote: “. . . I never knew them to make any distinction between me and themselves in any respect whatsoever. If they had plenty of clothing, I had plenty; if we were scarce of provisions, we all shared one fate.” Although exceptional, his treatment was not entirely unique; but for every such account there are hundreds which reflect the terrors of the day.

Smith’s adventures and observations during five years of captivity, spent mostly in the area that became Ohio, are fascinating and telling, as when he recalled an exchange with one of his adoptive brothers during a hunt. . .

I remember that Tecaughretanego, when something displeased him, said, “God damn it!”

“Do you know what you have said?” I asked him once.

“I do” – and he mentioned one of their degrading expressions which he supposed to have the same meaning.

“That doesn’t bear the least resemblance to it – what you said was calling upon the Great Spirit to punish the object you were displeased with.”

He stood for some time amazed. “If this be the meaning of these words, what sort of people are the whites? When the traders were among us these words seemed intermixed with all their discourse. You must be mistaken. If you are not, the traders applied these words not only wickedly, but oftentimes very foolishly. I remember a trader accidently broke his gun lock and called out aloud, ‘God damn it!’ Surely the gun lock was not an object worthy of punishment by Owaneeyo, the Great Spirit.”

• Daniel Boone’s birthday is considered to be on October 22 by most (although many consider it to be on November 2). Being long-lived (1734–1820) and a household name even in his own time did not spare the legendary pioneer and explorer the defining tragedy of the period. Although respected by colonials and Indians alike, Boone could not spare his children from the danger of the times. The ambush and death of his 16-year old son James in a 1773 massacre is as strong an account as can be found in any history.

Murdered horribly with five others near what is now Stickleyville, Virginia, James Boone had been sent ahead of the main party of a group led by his father which had followed him up from the Yadkin Valley in North Carolina in his first attempt to settle the vast western expanse known as Kentucky, “the garden of the West.” There had been no sign of hostile Indians, but in the early morning of October 10, the young men were attacked by a war party of Delaware, Shawnee and Cherokee Indians. Based on vivid description by the only survivor, by early December “the attack was reported in newspapers as far away as Baltimore and Philadelphia.”

Perhaps most horrific in the account was reported in the Middlesboro Times News (Kentucky) on February 21, 1951: “Among the band was an Indian, called Big Jim, who had often visited the Boone home in North Carolina. Young James pleaded with him to show mercy, reminding him of the friendship his father had shown him. But all to no avail.”

Whether or not he was in this party that turned back, as some have said, or the second one which successfully made its way to the new territory 18 months later. . . “There is little doubt that it was on account of his association with the famous Daniel Boone that (the elder) Abraham Lincoln went to Kentucky. The families had for a century been closely allied. There were frequent intermarriages.” – John Nicolay (1832–1901), Secretary and biographer of President Abraham Lincoln.

Although the buffalo and great elk hunted by James Smith and Daniel Boone are long gone, old myths of the South – both colonial and Indian – frequently refer to the relationship between special souls and the deer of the forest. Around the Alleghenies, the Appalachians, and the Blue Ridge Mountains, “those western lands east of the Mississippi,” large numbers of deer still roam, still ranging free and unfettered.

When glimpsed at a distance, especially under moonlight, or a wide fiery sky above the mountains at sunset, there is something somehow reassuring in the sight of these creatures; perhaps because they connect us to a part of all that occurred with the early Americans in those parts.

– Finis –

About Mr. Lincoln’s Movie(s)

By Richard Salzberg © 2012

_________________________

As far back as “The Birth of a Nation” in 1915, no less than 20 actors have portrayed Abraham Lincoln on the big screen. Notables having essayed our 16th president in film include John Carradine; Walter Huston; Henry Fonda; Raymond Massey; John Anderson; Jason Robards; Hal Holbrook; and most recently, Daniel Day-Lewis in Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln.”

Some actors played Lincoln more than once, including Massey, Anderson, and Frank McGlynn, Sr. (who had the role in three different films in the 1930s); and, in the mysterious way of the serious actor’s work, it is assurable that all who interpreted the legendary figure had at least a partial first-hand glimpse into the spirit of the great man.

However it is Carl Sandburg (1878–1967), poet, musician, folklorist, and three-time recipient of the Pulitzer Prize – and the foremost Lincoln biographer – who clearly, among all of those who never met the man, understood him best.

Through an intermediary in December of 1940, Hollywood producer Walter Wanger expressed an interest in Sandburg helping with a bio-pic on explorer John C. Frémont, “the Great Pathfinder,” and Union general. Considered to be “among the more literate and socially conscious American film producers of his time,” Wanger (1894–1968), had a career spanning decades, beginning with the Marx Brothers’ “Cocoanuts” in 1929, and ending with Elizabeth Taylor’s “Cleopatra” (1963).

Carl Sandburg, 1938

Although that collaboration never occurred, in a letter to Wanger dated December 14, 1940, Sandburg wrote: “One reason I am willing to work on a Fremont picture, aside from its personal appeal, is that during the time we worked on it, we could talk over the field of a Lincoln picture. I think I know why the (Ray) Rockett film, the Griffith, the Sherwood-Massey failed to go over. It might be that I could lay before you a number of Lincoln scenes that would have their point for the crises that lie ahead the next few years. We would have no understanding at all that there is to be a Lincoln picture. Yet it might be that with a few long discussions, covering a thousand possible angles, we would arrive at a Lincoln story that would become a classic. My own approach to a Lincoln book has always been slow and tentative. Perhaps I mean that you and I could make some reconnaissance flights – afterward deciding whether to attack.”

Dahlgren’s Raid: And Memories of Things Unknown

By Richard Salzberg © 2012

____________________________

“To be lost is only a failure of memory.”

– Margaret Atwood

Scottish author and historian Alistair Moffat frequently references and utilizes “toponymy” in his work. Having to do with “the place-names of a region. . . especially the etymological study of them,” toponymy is an amazing tool for researching the myriad mysterious worlds of ancient Celtic kingdoms. The study of place-names can also be an excellent device for discovering the past in the more remote corners of our own regions. Although, countering that, there seems little to be discerned from the name of Stevensville, Virginia, other than a reference to a founding family.

However, as surely as morning mists shroud the Highlands, there are other signs near that tiny hamlet (population: 158) in King and Queen County which can provide clear indications of momentous things that happened there. For one, the unusual number of ravens which seem ever present at a lonely spot not far from the old crossroads, near a roadside history marker with the bold capitalized heading: “WHERE DAHLGREN DIED.”

As with a surprising number of other Civil War sites throughout the South (although perhaps still too few), the spot marking the end of Dahlgren’s Raid is relatively as remote today as it was on March 2, 1864, when, as the historical marker states “. . . after the raid on Richmond, his forces bivouacked here and in breaking camp he fell to the fire of Confederate detachments and Home Defense forces who had gathered during the night.”

As with a surprising number of other Civil War sites throughout the South (although perhaps still too few), the spot marking the end of Dahlgren’s Raid is relatively as remote today as it was on March 2, 1864, when, as the historical marker states “. . . after the raid on Richmond, his forces bivouacked here and in breaking camp he fell to the fire of Confederate detachments and Home Defense forces who had gathered during the night.”

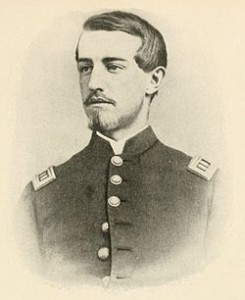

The subject of this metal inscription is Ulric Dahlgren. Born to privilege and respectability as the son of Admiral John A. Dahlgren in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, in 1842, it could be that Ulric Dahlgren would have had a life of civic accomplishment and noblesse oblige – were it not for the sirens’ call to war. His father wanted him to be civil engineer, and the son even briefly embarked on efforts in that direction; but that was not to be.

The Continuity of Oaks

by Richard Salzberg 7/21/2012

For the ancient Druids, the oak was a sacred thing. As described in Alistair Moffat’s remarkable book “Before Scotland,” when the Romans moved to conquer Britain and destroy the Celts two thousand years ago, after having identified the influence of the spiritual and cultural leadership of the mysterious priestly Druids in what Moffat cites as “a matter not of conquest but of annihilation,” the Romans made a point of decimating countless groves of primeval oaks throughout old Caledonia as a key part of their strategy.

So it may be that when a venerable, lifetimes-old oak is shattered and falls to the ground, it is not unreasonable to consider that subliminal aspects of race memory are part of the great sadness, and, yes – the mourning.

A fierce black storm came through the Roanoke Valley on Friday night, June 29. It blew in quickly from the west at about 9 o’clock, surreal in its power and ferocity and without so much as a single drop of rain.

Among the thousands of trees and limbs that came down that night, tossed and splintered in the dark whirlwind, was a massive oak which had served faithfully for 150 years or more; first as a guardian for rolling pastureland, and later as a massive sentinel at the curve of a narrow neighborhood road.

The great oak fell in the night, broken into great pieces that took down other large, good trees and power lines, and closed the narrow road for several days. We are told to remember that, as a living thing, a tree has a life span, with a seeded birthing and an inevitable passing. (“When it is time, it is time.”) But the great oak fell, and now is gone; and feelings of great loss and sadness are part of the memory of that life.

With all of its violence, the storm passed quickly to the northwest. The next morning the sun was out, bright and very hot. Birds flew and sang as if nothing had happened. And surely that evening the deer came out as they would, although their paths had been altered by the falling of the trees; and there will no longer be a harvest and feast of sweet acorns for them at this place in the Fall.

Of course, the loss of a single tree is in no way comparable to the terrible loss of lives and homes from past violent storms and tornadoes, such as those that devastated entire communities in other parts of Virginia, the Midwest and the deep South. Beside the inestimable loss of so much by natural conflagrations (and, for that matter, the loss of life and limb for so many of the young Americans who fight our wars), to mourn a single tree might seem indulgent and even supercilious.

The people of Missouri, Alabama, and western Virginia, and too many other places are having to make the best of their woeful, storm-tossed circumstances. It will take years to adjust and rebuild from the destruction. However changed and continually touched by alternating shades of hope, despondence, anger, musing, and trepidation at the rumble of thunder or a sudden high wind before the sight of a dark pewter sky – and an indelible sense of loss – their lives continue. They will persevere as people have since time immemorial.

In the days following the fall of the great oak, the new expanse of sky and the land now revealed below the ridge seem very harsh to the unaccustomed eye. “It is only the loss of a single tree,” it can be said, but as a symbol for all that this loss represents, for our own time and for uncountable millennia – the great oak remains powerful.

¶ ¶ ¶ ¶