The Miracle of Providence Spring

By Richard Salzberg / ©2017

The grievous conflict of the Civil War remains the most convulsive, destructive, and still compelling chapter in the nation’s history. By 1864 the conflict was in its third year, and the North’s strategies, in combination with its resources and resolve, had begun to finally subdue the South. Union victories on the battlefield had grown more numerous, and the war of attrition as envisioned by Lincoln, along with the Anaconda Plan as originally conceived by Winfield Scott, were proving brutally successful. An extension of the attritional war included the decision by Lincoln and General Grant to put an end to what had been large general exchanges of prisoners-of-war between the two sides. This action succeeded in further eroding the manpower which had become the Confederacy’s last natural resource, while it also resulted in tens of thousands of soldiers from both armies languishing hopelessly in what became little more than death camps in both North and South.

Despite the unconscionable conditions which existed in the prison camps of both sides, the Confederate prison at Andersonville, Georgia has come to symbolize the worst of all of the camps; and, by extension, it serves to represent the very worst aspects of America’s vicious war between countrymen and brothers.

Andersonville is about 110 miles south of Atlanta. From its inception as a prison camp in February of 1864 until the war’s end in April of 1865, a total of 45,000 Union prisoners-of-war passed through its gates. As many as 32,000 men were interned there at one time. In a vast outdoor pen of about 26 acres, surrounded by a 15 foot-high stockade made of upright rough-hewn pine logs driven straight into the ground, those poor souls within its confines were provided with little food, and no shelter whatsoever. The winter months were cold and relentless, and in summer the scorching sun and heat were deadly for the already weakened captives.

Men who arrived without tents or blankets, or any crude utensil needed for the digging of hovels into the hard red Georgia clay died unattended on the open ground; and from the very first, prisoners died by the hundreds.

Untreated wounds and disease, the incessant hunger and thirst, as well as a mortal despair, all combined to leave the tragic legacy of a death toll of more than 13,000 men. What had been the sleepy railroad town of Andersonville became a name synonymous with a veritable hell on earth, a nightmare of unimaginable dimension, unreal and impossible to ever fully describe even by those who were there.

Andersonville

By 1864 food was scarce throughout the South, and scarcer still for the ill-fated Union prisoners. But, as is ever the case in the history of such human misery, it was the lack of water and the torture of continuous thirst which became most destructive to body and mind. At Andersonville there simply was not enough water for so many men. In fact, because of poor planning and design, and the influx of such unexpected numbers, there was no clean water at all.

Stockade Creek was the name for the pitiful stream which ran through the lower third of the prison ground. With the exception of several small wells dug by prisoners, it was Andersonville’s only source of water; but before it ever entered the prison it was befouled by the cooking and contamination from the adjacent Confederate guards’ camp outside the stockade. The low banks and areas all around Stockade Creek became a vast and fetid morass in a very short time, for it was also used as the prison’s open latrine.

With no officers among the unfortunates at Andersonville, there was no formal leadership or organization. The basics of survival became the responsibility of the individual prisoner, and the sole occupation of each man. Beyond the deathly sick and the wounded, those without any sort of personal purpose or direction were inevitably the first to die. Within such an incubator for the worst sort of human suffering and misery, the actions of the individuals at Andersonville ranged from the extraordinary to the unforgivable.

While some prisoners became part of the feared gangs which organized to exploit and brutally prey upon their comrades, such as the notorious “Andersonville Raiders,” other men dedicated themselves to providing as much assistance and comfort as possible to the infirm and dying. Also, as the long months passed within the camp, religious activities became an important part of many of the prisoners’ lives. Interest in prayer meetings and growing attendance enabled them to be held each night in different parts of the camp, and preachers of all sorts emerged from the desperate ranks to hold services and to minister to the wavering hopes and spiritual needs of the forlorn men. An Andersonville Sunday School was even established; and even as the camp’s horrid conditions became worse, the numbers of the faithful grew.

June and July of 1864 brought weeks of searing heat, and the number of dead steadily grew. Loaded in crude carts and carried outside the stockade to what was known as the Dead House, they awaited a primitive mass burial in the long, shallow trenches dug by their comrades. Such was the particular hell of Andersonville that, although surrounded by tall Georgia pines, the prisoners had no wood to boil the filthy water; and in the midst of what had once been rich farmland, they had no food. And men within the stockade were dying from thirst only yards from the clear, free-flowing waters of Sweetwater Creek which ran just outside of the south wall of the prison.

But in early August the rains came.

The blessed relief began as light showers which came down and rinsed the mass of 30,000 prisoners as they lie about the seared open acreage. Then, as the rain grew stronger, the men looked skyward and opened their parched mouths. Soon, all those who could began to hold up battered canteens and tin cups, and any other vessels they could find to hold the clean, precious rainwater. The downpour soon became a torrent which soon turned the prison’s 26 acres into a vast quagmire. As the heavy rains continued, Stockade Creek rose higher, overflowing its banks and carrying away large quantities of the camp’s accumulated filth and mire with its strong new current.

Survivors testified after the war that the stream rose five feet in one hour. Eventually the surging water carried away portions of the east and west stockade walls. Although the Confederates hurried to arms in anticipation of the threat of a mass escape, the prisoners were simply too weak to much more than avoid the rushing water, and to revel in the relief from the torments of thirst and the burning sun.

After five days of intermittent rain, on August 13, the great cloud appeared. Distinctive for its tremendous size and sharply defined shape, it was said to be like a giant mountain in the sky, its color like that of blued gun metal. Approaching from the east, the cloud moved slowly westward until it was directly over the camp. As thousands of men watched with a growing sense of awe, it seemed to stop and hover directly above the bough-covered Dead House, before moving slowly towards the North Gate.

Even the nervous guards were compelled to stare in wonder as the cloud loomed, over the prison, still and powerful. By this time most of the camp’s crude shelters had been washed away by the rains, and the prisoners had been soaked to skin for days. Now, as the emaciated men stood staring heavenward, for the first time at Andersonville Prison there was complete silence. Even the endless drone of misery from the sick and dying became muted, then seemed to disappear. As the cries of suffering quieted, a soft rain could be heard falling gently upon earth and man.

Suddenly, there came a thunderous, deafening roar. From men who knew the sound all too well, it was said to be like the explosion of a thousand cannon. It was so powerful that the weaker men standing near the west wall were thrown to the ground. Then, from the heart of the deep blue cloud, came a great, blinding flash – followed nearly immediately by searing bolt of blinding white lightening. It too exploded from the sky, violently striking the earth just within the stockade at a notorious point known as the Dead Line, beyond which no prisoner could pass without being shot. At the place where the fiery lightening struck there was another tremendous explosion, and a stunning eruption of earth and steam filled the air. Instantly, torrents of fresh water gushed from the blasted, broken ground, pouring forth and coursing into the prison. This awesome water was cool and clean, and its flow was to become a permanent thing.

The thunderous lightening had found the highest point of an underground stream, and the name of Providence Spring emerged nearly as quickly as the waters came forth to the relief of the thousands.

Providence Spring at Andersonville today

On that same day the rains stopped, and the stockade walls were soon repaired. No attempts at mass escape were ever made, nor any effort made for the prisoners’ liberation by Union forces, even when Sherman’s army was within 20 miles of Andersonville on their “March to the Sea.” The imprisonment and harsh conditions for thousands of Federals continued through another long winter, and until the war’s end in April of 1865; but throughout that entire time the miracle waters of Providence Spring continued to flow at the rate of about 10 gallons per minute. All who were there knew how rare a thing it was, but among the religious and newly religious in the camp, there was the special knowledge that the prayers of men in the most desperate sort of need had been answered. The awareness and belief that plaintive supplication could be heeded from even such a forsaken and miserable place as Andersonville was infinitely gratifying.

Shortly after war’s end, Clara Barton and a former prisoner by the name of Dorence Atwater went to Andersonville as leaders of a dedicated group whose mission was to exhume, identify, and then properly rebury the scores of Union dead from the mass graves. Atwater, known as “the Clerk of the Dead,” had worked in the Dead House and somehow managed to record and secrete thousands of names. Incredibly, all but 400 of the 13,000 men who died there were successfully identified by this inspired effort. In the midst of such gruesome work in the sweltering heat of a burning July, those courageous and inspired humanitarians joined the prisoners who had gone before them whose bitter thirst had been quenched by the cooling, mysterious waters of Providence Spring.

Today, Andersonville is a very quiet place. Still a part of the rural Georgia countryside, it is a National Historic Site administered by the Park Service. There is a modern Visitors Center with affecting displays that communicate the tragic history of the place effectively. There is also the Andersonville National Cemetery. Originally dedicated by Clara Barton’s group in 1865, the cemetery continues to provide a final resting place for American veterans today.

A visitor to Andersonville today can tour the 515-acre expanse by foot or by car. Beyond the modernities, once close to the impressive site of the actual stockade, one rather surprisingly becomes aware of a pervasive sense of rare quietude, as a curious sort of peacefulness seems to emanate from the place. It is as if the fiery heat of a great mythological furnace had somehow burned away all of the worldly dross from this one sacred point on earth, leaving an area of serene tranquility. When asked about this impression, a receptive Park Ranger acknowledged that even in summer there comes an unexpected, cooling breeze from the west; and during the coldest of Georgia winters, the area within the lines of the stockade always seems to be a bit warmer than anywhere else.

Walking the now cleared, rolling land where so many men had been left to their fates and struggled to survive in such deadly misery, one can still see traces of half-dug wells and hovels scratched nearly by hand in the hard red Georgia clay, and the remnants of hopeless efforts at escape tunnels. There are also the more recent covered trenches of the archeologists who have discovered large pieces of the stockade’s original wooden palisades beneath the earth; and since 1987 the National Park Service has reconstructed portions of the stockade to “enhance visitor understanding of the prison and prison conditions.” And along the lower portion of the boundary of the west wall, just below the North Gate, there is an impressive shrine made of rough-hewn granite stones surrounding a fountain. With an appearance like a small chapel, it was built and dedicated in 1907 by Union veterans and survivors of Andersonville. The memorial rests at the mouth of Providence Spring, and the clear water still flows at the rate of about 10 gallons per minute. The water there is always cool, and is said to be especially invigorating.

The symbols of the history of our relatively young nation are continually threatened by unconscionable development and ignorance, but meaningful places possessed of great spiritual resonance still exist throughout the land. Of such sites, Andersonville is easily among the most prominent. For those who are aware of it, there is a responsibility to learn from the entire experience, to share the saga with others, and to urge a visit.

To know the story of the Miracle of Providence Spring is to understand that there remain accessible, powerful mysteries and rarified spaces where rare things have occurred, and where they continue to resonate on what can only be described as hallowed ground – at least at a place called Andersonville.

– Finis –

Gustavo Franco [1958 – 2013]

“To F . . .”

Beloved! amid the earnest woes

That crowd around my earthly path –

(Drear path, alas! where grows

Not even one lonely rose) –

My soul at least a solace hath

In dreams of thee, and therein knows

An Eden of bland repose.

And thus thy memory is to me

Like some enchanted far-off isle

In some tumultuous sea –

Some ocean throbbing far and free

With storms – but where meanwhile

Serenest skies continually

Just o’er that one bright island smile.

– Edgar Allan Poe (1835)

Jewish Queen Gudit of Ethiopia

By Richard Salzberg ©2013

Everybody needs his memories.

They keep the wolf of insignificance from the door.

― Saul Bellow

_____________________________________________

“Why do they even bother with the word ‘Deli’ here?”

“In the name?” He laughed, “I thought you liked this place.”

“I do,” she replied. “It’s just confusing.”

“What do you mean?”

“It’s about as Jewish as Easter, that’s all.”

He was still smiling. “So now there should be a law about use of the word ‘Deli’ and appropriate Jewish ownership?”

“Maybe. . .” She had been smiling all along; now, with mock seriousness, “Maybe we should look into that.”

“The food’s good anyway.”

“Yes, it is.” She found the squeeze bottle of dark mustard among the condiments on the table and opened the onion roll that enclosed her turkey and Swiss. “But I mean, really – they don’t even have latkes on the menu, for Christ’s sake.”

“Maybe that should be the law,” he said: “No latkes, no use of ‘Deli’ in the name.” He put some regular yellow mustard on his hot dog and took a bite, chewing thoughtfully before speaking. “This is however an excellent kosher frank.”

“Good. Enjoy . . . and let me hasten to say this is a very nice turkey sandwich, kosher or not.”

“Speaking of Jews and delicatessens. . . I’ve got a question.”

“Let me guess – ‘Did Jesus really eat latkes?’ ”

“No. . . but I like that.”

“So what’s the real question?”

“What year is it?”

“2012.”

“No, really. . .”

“2013.”

“I mean what Jewish year is it?”

“So that’s why you brought me to this ersatz deli?”

“Of course that’s why – !”

She took a waffle chip from his plate. “We just entered the year 5774.”

“That’s a very long time.” He poured more cream soda into his glass of crushed ice.

“A long time for what?” She took another chip from his plate.

“For all that Jewish stuff.” They both smiled at the line.

“Yeah, I guess you’re right.” She was still smiling. “These are very good potato chips.”

“Help yourself.”

“Since you brought it up, old boy, I do have an interesting Jewish item for you.”

“Good. Bring it on.” He took another sip of the cream soda and politely suppressed a belch. “It must be Kabbalah related.”

“No,” she replied thoughtfully. “Better actually, and a bit more esoteric than whatever year it is.”

“Do I have to join anything?”

“No.”

“Do I have to sign anything?”

“No. . .” She took a small notebook from her bag and opened it to a page marked with a small iridescent post-it. “Not today anyway.”

“Oh, no – what is it with you and the notebooks? Just like your brother.”

“We just don’t want to forget anything important.”

“So you write everything down. . .”

“Not everything.” She shook her head in a practiced way that easily reset her hair. “Now just listen. . . this is from the Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London (Volume 63, Number 1, 2000) – ”

“Oh, my. . .”

She gave him a look and continued reading: “It is well known from relatively recent Ethiopic tradition that Ethiopia was once ruled by a queen called Gudit, Yodit, Isat, or Ga’aw, with both positive and negative characteristics. On one hand she was a beautiful woman of the Ethiopian royal family, much like the Queen of Sheba, and on the other she was a despicable prostitute who, at a time of political weakness, killed the Ethiopian king, captured the throne, and as a cruel ruler destroyed Aksum, the capital, persecuted the priests, and closed the churches.”

“That is. . . absolutely fascinating.”

“In some anglicized accounts she is also known as Queen Judith.”

“Ah, no wonder you can relate to her! When did all this occur?”

“Sometime during the mid-900’s, about 1100 years ago. Queen Gudit reigned for about 40 years.”

“That’s crazy. And she was black?”

“Hey – this is not H. Rider Haggard stuff – of course she was black!” She smiled and slightly shook her head again. “She was likely descended directly from Solomon and Sheba, who came maybe 2000 years before her.”

“This is too much to compute.” He took another bite of his hot dog. “Who else knows about Queen Gudit, or Queen Judith?”

“The Ethiopians.”

“I should have guessed.”

“Especially the Ethiopian Jews, the Falashas. Mostly all coming from their very strong oral traditions. She was looking through her notebook. “Here’s one more thing. . . ready?”

“I guess.”

“There were also some reliable accounts by contemporary Arab historians.” She looked at him. “They were good back then. This is from a guy named Ibn Hawqal. Listen. . .” she began to read. “The country of the Habasha has been ruled by a woman for many years now: she has killed the king of the Habasha who was called Had’ani. Until today she rules with complete independence in her own country and the frontier areas of the country of the Had’ani, in the southern part of the country of the Habashi.”

“Where do you get this stuff?”

“Here and there, and for this kind of thing there are always at least a few earnest European academics and Orientalists, usually Brits.”

“It sort of reminds me of ‘David and Bathsheba.’ ”

“Of what – ?”

With feigned incredulity, “ ‘David and Bathsheba’ – the movie.”

She nearly moans. “Oh, my God. . .”

“Gregory Peck and Susan Hayward. 1951. I just saw it on TV. It’s not bad.”

“I must really be boring you?”

“I was kidding!” He looked at her plate. “How’s the cole slaw?”

“It’s very good,” she said. “Here – you can have the rest.”

“No,” he replied with mock humility. “I couldn’t.”

“Have it. I already took what I wanted.”

“Thanks,” he said, using a spoon to help himself. “So tell me more about Queen Gudit.”

“Yeah, right.”

“I’m serious – it’s fascinating.” He took a taste of the slaw. “And this is delicious.”

“I will tell you this. . . the Jews in Ethiopia can trace their Judaism so far back it wasn’t even recognizable at first by the Jewish establishment. They call themselves Beta Israel – ‘House of Israel’ – and their version of the faith is the most ancient, pre-Ezra – you know, Ezra?” He shrugged and took some more cole slaw, and she continued, “One could say that in ancient times Ethiopia was a Jewish nation. . . their traditions go back to the time of the First Temple. That’s how deep their Judaism is.”

“And Queen Gudit was either a devil or a beauty queen warrior?”

“Whenever the goyim write the history, the Jews are always the devil. You should know that.”

“You mean I should know that because of one Jewish grandparent?”

“That would have been enough for the Germans, brother.”

“This is all too heavy. I just wanted to grab a bite to eat.”

“Finish your chips, you’ll feel better.” She took one from his plate, using it to accompany the last bite of her sandwich. “One last thing. . .”

“Oh, God. . .”

“There are about 130,000 Ethiopians living in Israel today.”

“Really? Falashas?” He was impressed again with all that he did not know, but the instinct to appear clever supplanted that. “Living like kings, I suppose,” he smiled, “ – or maybe queens?”

“Well, not exactly.” She said with a sigh. “The Jews are marvelous exclusionists, you know, and the normative Jewish establishment has always been masterfully cynical. But the Falashas are there now, God bless them, formally recognized as Jews for the Law of Return; and they’re making a tremendous contribution to Israeli society.” She looked around for the waitress. “Can we get some coffee?”

“Sure,” he said, searching the room.

“How the Ethiopians got to Israel is an incredible saga in itself. A very courageous story. . . and you know, they can all be said to be descendants of the good and mighty Queen Gudit.” She took the last potato chip.

“Like I said. . . ” he found the waitress and got her attention, “it’s fascinating.”

“By the way, the winner of the Miss Israel pageant for 2013 came from Ethiopia with her family when she was twelve.”

“She must be gorgeous.”

“Beautiful. . . she looks just like a queen,” she said. The waitress came to the table and they each ordered an espresso.

“Wait,” he said, catching the waitress as she was about to leave with the empty plates. “Thanks.” He turned to Judith and asked, “Want some dessert?”

“No, thanks,” she replied. “I’m fine.” The waitress left, and she thought for a moment before speaking. “Have you ever heard of the Ibos of Nigeria?”

“Who – ?”

“The Ibos of Nigeria?”

“No, who are they?”

“They might also be members of the tribe.”

“Which tribe?”

“The Jews. . .”

– Finis –

_________________________________________________

See more at:

1] http://www.dacb.org/stories/ethiopia/gudit_.html

2] http://forward.com/articles/14317/the-ibos-of-nigeria-members-of-the-tribe-/#ixzz2fWve7Vz5

“What is a Dolmen?”

By Richard Salzberg ©2013

“It was crazy,” he was saying. “You know, we hadn’t seen each other in, like, 25 years. And yet, honestly, in a way, I felt closer to him as a friend than with a hundred friendships that have come and gone during the same time.”

“Really?”

“Yeah.”

“Why do you think that is?”

“I don’t know.” He moved his chair closer to the table. “I guess because of the distance. ‘The safety of distance.’ He’s in Spain and I haven’t been back there in all that time. Too long . . .”

“I thought you said he was English.”

“He is. Or was . . . but I guess you’re always English, right? Anyway, he’s lived in Spain for about 40 years. He was one of the young wanderers who went to Spain looking for ‘adventure and whatever comes our way.’ Then he fell in love and married a pretty señorita. They raised a beautiful little family there, and he’s done alright for himself as a trader and translator.”

“That’s how you met, right?”

“Right, he was a translator for some wildly aspirational stuff we were trying with some Spaniards a hundred years ago.” He quickly braked the musing. “Anyway . . . Michael’s a very clever cat. And when we finally get together to reconnect, it’s at a bar in a hotel in Lisbon.’

“That’s cool.”

“And then we spent a lot of the time discussing the dolmen he’s got on what he refers to as ‘his wife’s family’s property.’ ”

“Where’s that?”

“They have a finca – ”

“– what’s that?”

“It’s a place in the country. They call it “El Palancar.” Very rugged, beautiful land about seven miles from the Portuguese border, near the town of Valencia de Alcántara. From their land you can see an ancient Portuguese mountain village called Marvão.”

“So you finally got together and discussed a what – a dolmen – ?”

“Yeah.” He paused before deciding not to try to explain. “Yeah . . . it was really good to see him again.”

“I can imagine. And you said he knows a lot about American culture.”

“Yeah. Yeah, he’s very big on American politics and jazz. And track. He knows all about American track, for Christ’s sake.” He laughed, “Do you?”

“Sure. Everything.”

“Exactly. But track is a big thing over there, and he used to be a runner. He’s also a Class-A bird watcher, mostly in the wild, and a hell of a photographer. Anyway . . . we finally get together in person after so long, and it was really good. I really believe that by continuing to communicate over the years, first by mail and an occasional phone call, then by e-mail of course . . .’

“Of course. And now Skype.”

“Of course! After having met years ago as a couple of hopeful young guys . . . I don’t know . . . it was like we sort of kept each other young.”

“Yeah, right,” he laughed.

“Okay, maybe that’s overstating it. But really, there’s something slightly metaphysical about it.”

“That’s a good word.”

“Yeah.”

“So you were going to tell me something about World War II.”

“Ah, yes . . .” He absently wiped away a small ring of condensation left by his glass with the square bar napkin. “Well, it’s maybe not so much about the war as it is a thing about . . . I don’t know . . . like a general sort of eternal thing between sons and fathers.”

“Oh, great . . .”

“I know, I know . . . I’d just written a short thing about a book I read, “The Burma Road” [www.facebook.com/highbridgepublications] by Donovan Webster. It’s all about – ”

“– the Burma Road!”

“Brilliant!” He smiled and finished his drink. “Anyway . . . I remembered that Michael’s father had served in Asia with the Brits during the war, and . . .”

“You remembered that – ?”

“Well, yeah . . . in 25 years of dialogue you can cover a lot of ground. He had e-mailed me an old photo of his Dad looking like a lean British cowboy standing in front of some ancient stone temples somewhere in Southeast Asia.”

“That’s weird.”

“Well . . . after all – what ain’t?”

“You’re right there.”

“Anyway . . . I’d been reading about all this terrible grueling stuff along the Burma Road, and the Ledo Road – all along ‘700 miles of World War II’s longest active battlefront’ – all about Orde Wingate and – ”

“ – who?”

“Look him up . . . so I’m reading about how Orde Wingate created this outfit that became these incredible bad-ass British jungle fighters who kicked Japanese ass all over hundreds of miles of the most lethal sort of terrain around Burma, Thailand, China, and India. They were driven to get even for Singapore, and Hong Kong, and everywhere else they had folded, right? And I remember this crazy sepia photo of Michael’s Dad, and when I see him I ask if by some chance the old man had been with the Chindits.”

“With who – ?”

“The Chindits. That’s what these British guys were called. Chindits.”

“What does it mean?”

“Look it up.”

“Okay, professor . . . so what about his father?”

“Here’s what he told me,” he said, unfolding a piece of paper from his pocket.

“You wrote it down – ?”

“I try to write down everything I should remember.”

“Good idea. Practical, too.”

“So in this very short thing about the book I used the line: ‘Do talk to our fathers when we can,’ and what Michael said about his old man was important. I mean here we are in a bar in Lisbon after 25 years, and we’re trying to still feel (and act) like young men . . . but our fathers were in a war already relegated to history books.”

“And the History Channel.”

“Right.”

“And they were younger then than anybody could ever remember.”

“Especially themselves.”

“So what did your friend say?”

“Wait a minute,” he looked around the room.

“What?”

“I need another drink.”

“Oh, man . . .”

He got the waitress’s attention and ordered another drink. “It’ll be worth it.” When it arrived he thanked the woman and took a sip. “That’s better,” he said, looking at the paper again. “Now then . . .”

“Did your friend Michael see you write this down?”

“I guess so.”

“What did he think?”

“Who knows?” He took another taste of his drink. “Do you want to hear what he had to say about his father, or not?”

“I’m still waiting.”

He began to read from the paper: “My dad was in a regiment called the Royal Signals. All I know is that he knew Morse code and saw action in Burma and went back to India to Poona, I think, in between battles. Didn’t tell us much more except for that occasion when he told me about having to use flame-throwers to flush Japanese out from a bunker. He went to India (via South Africa) when my mother was expecting their first child, my eldest sister Jean (still going strong), and he didn’t actually see her until she was three, only in photos. All letters were censored (my mother kept them all) and I’ve seen some, but there’s no indication of where they were, what they were doing, ‘nowt at all,’ as we say in Yorkshire. I think he could drive a tank, but once back in Britain he never had a car. He always went to work (textile factory) on his bicycle.”

“Whoa . . .”

“Exactly.”

“I think I need another drink now,” he said, signaling the waitress.

“Go ahead.”

“I just have one question . . .’

“Shoot.”

“What is a dolmen?”

_________________________________________________

See:

1] http://www.worldwar2history.info/Burma/Road.html

2] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chindits

3] http://www.nationalww2museum.org/see-hear/collections/focus-on/merrill.html

4] http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Dolmen

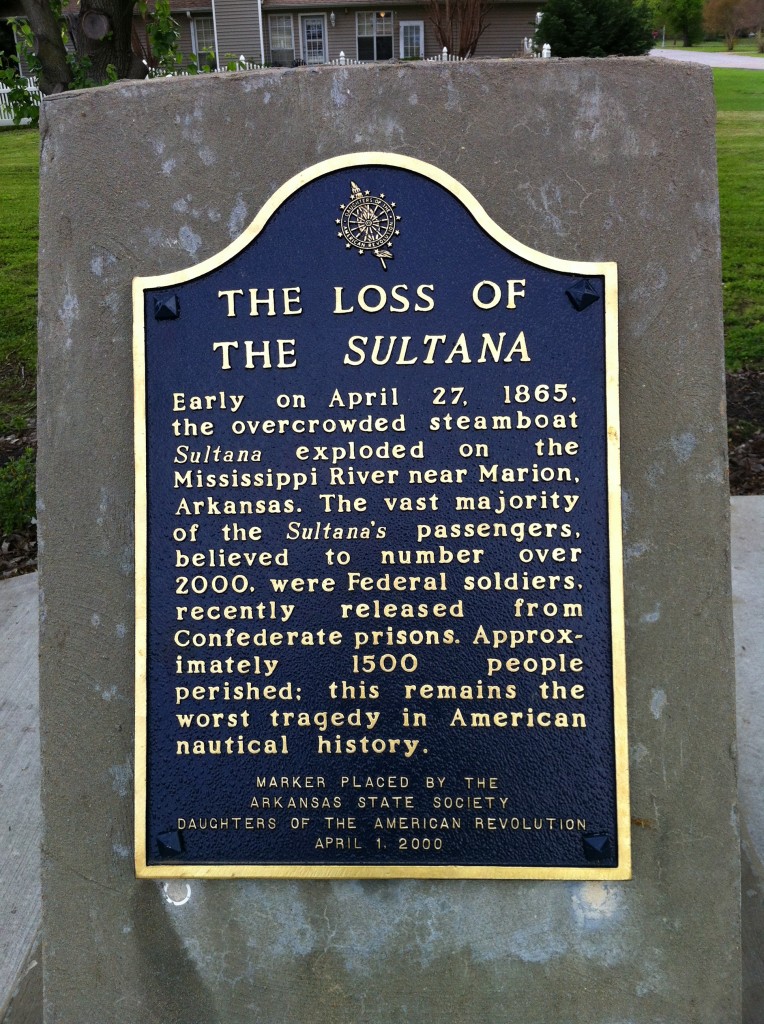

April 27, 1865: The Greatest Maritime Disaster in US History

By Richard Salzberg © 2013

It was another of those impromptu Civil War roundtables on Wednesday night at the new library and it was going well. Egos and the one-upmanship remained generally in check, and everyone was attentive to the exchange of good information. Nobody knew who the attractive white-haired woman was; but she was respectful of the group, listened intently, and seemed knowledgeable.

As the topic veered to the treatment of prisoners of war and the respective conditions for North and South, it was iterated that the death rate for Southerners at places like Elmira and Point Lookout was indefensibly nearly as high as that for Northern prisoners at Andersonville. The woman agreed that the Federals had to share in the responsibility for the tragedy of Andersonville when they put an end to the prisoner exchanges, and particularly when Sherman could have liberated the poor souls when he came so close to the prison during his “march to the sea.”

The woman actually seemed to know a good deal about Andersonville. When a retired history teacher brought up the recent archaeological work there, she mentioned Providence Spring [http://ow.ly/mCusz]; and after a bit more of the statistical back-and-forth, she stated politely but unequivocally that one cannot be fully informed about Andersonville without knowing about the SS Sultana.

No one among the group of six or seven men (none of whom knew who the woman was) disagreed; and, if truth be told, few if any actually knew much about the tragic saga of that paddle-wheeled steamboat which once plied the Mississippi River. When the woman solemnly nodded and referred to “that old riverboat that sailed into hell with 1600 lost souls,” no one even thought of interrupting her.

“Lee surrendered on April 9, as we well know, and of course Lincoln was murdered on April 14. Then Joe Johnston’s army still in the field surrendered near Durham, and John Wilkes Booth was shot on April 26. The Sultana blew up on April 27. Although it remains the greatest maritime disaster in US History – ”

A man in a corduroy coat interrupted her. “ – the story was eclipsed by all the news just preceding it.”

For an instant the woman’s ice-blue eyes flashed with . . . something. Then she smiled and continued. “The Sultana left New Orleans on April 21. They were headed upstream at a time when the Mississippi was cold, running high and fast from the Spring melt-off, and soon they were having trouble with the boilers. When the boat docked in Vicksburg on April 24 – ”

“Vicksburg?”

“They had been contracted to pick up Union soldiers recently released from Andersonville, and some smaller Confederate prisons. And there were other soldiers just discharged who wanted to get home as fast as they could. The Federals were paying steamboats $5 per soldier for the trip to Cairo, Illinois.”

“That is fascinating,” the history teacher said.

A retired railroad worker spoke up, “It’s always all about the money.”

“While there,” the woman continued, “the captain decided to make cursory repairs to the boilers.”

“And they did a half-assed job.”

“Presumably,” said a crew-cut man who had not spoken before.

“Apparently,” said the woman. “But as is usually the case with such things, we’ll probably never be absolutely certain.’’

“Hell,” interjected a large man in a clean wrinkled shirt, “I still want ‘em to admit who really killed Lincoln.” The woman shot him a look, then smiled.

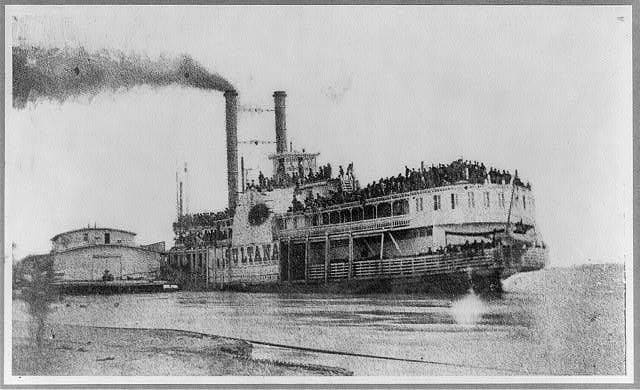

“Rather than replace the bad boiler they found, they did a quick patch for the leak and began the job of getting the soldiers on board.” She paused thoughtfully and touched her hair. “Now, we have to remember the state of most of these men. There hadn’t been time to recover from their deplorable experiences in the camps, and they just wanted to get home. The Sultana was legally permitted to carry 376 passengers. But by the time the boat left Vicksburg – along with scores of livestock brought up from New Orleans – there were more than 2400 people on board.”

“Incredible.” The man in the corduroy coat wrote something in his notebook.

The woman continued. “Emaciated men thronged every square foot on the boat. 2600 people and livestock crowded onto a steamboat with a seriously damaged boiler where less than 400 should have been. . .” She unfolded a piece of paper from her pocket and began to read: “The vessel was so densely packed that the crew had to shore up sagging upper decks with large timbers.”

“What did happen?” asked a man in a plaid shirt.“It blew,” said the railroad man.

“Sounds like the Maine,” commented the history teacher.

“I couldn’t hear you – the what?”

“The USS Maine. In Havana Harbor. 1898. ‘Remember the Maine.’ ”

“You mean sabotage?” The large man in the wrinkled shirt looked at the woman.

“We will never know,” she replied.

“Could have been sabotage,” the history teacher said. “Didn’t someone confess years later?”

“Whoa. . .” said the crew-cut man. “Think about it.”

“They were damn sure far enough down South.” It was the retired railroad man.

“The woman’s eyes flashed, then she shrugged. “We’ll never know.”

The history teacher sighed. “That is so frustrating.”

“All we can be certain of is the loss and the bloody horror of it all. At least 1700 people died horribly – including civilians and children. We can talk about sabotage, and we can talk about corruption. But all we really know is that.

Another man spoke for the first time. “What do mean ‘corruption’ ”?

“In 2001,” she looked down at her paper, “Stephen Ambrose wrote that the steamboat captains were paying kickbacks of $1.15 to the Union officers to fill their boats with men.”

“My God. . .” The railroad man’s first instinct was to be angry. Then he just felt very sad. “When is anything ever going to change?”

The woman continued to read: “On the night of April 24, at 9 p.m., the Sultana departed Vicksburg and headed north on the flood-swollen Mississippi River. The enormous weight of the passengers and cargo on the decks had the crew worried. William J. Gambrel, part owner of the Sultana, and soon to die, warned the Federal officer in charge on the ship that any sudden movement by the prisoners could cause the decks to collapse, and too many men crowding to one side of the deck could result in the boat capsizing. That horrifying scenario almost played out when the Sultana docked briefly at Helena, Arkansas. Word quickly spread among the passengers that a photographer was setting up his camera on the west bank of the river. When many of the soldiers hoping to be in the picture caught on film quickly moved to the port side of the boat, the Sultana began to list dangerously.” She paused and looked around the table. “You can still see the photograph. Hundreds of men crowded on the top deck of the doomed vessel. It was the last image of the Sultana.”

“Unbelievable,” spoke the crew-cut man, almost as if to himself. “And they all thought they were going home at last.”

She began to read again. “The boat made several other stops on its ill-fated journey up the Mississippi. Then, in the early hours of April 27, at a point where the river was nearly four miles wide about seven miles north of Memphis, Tennessee, three of its four boilers suddenly exploded.” She paused and looked at the faces of her listeners, then said. “Here I quote: ‘The blast tore instantly through the decks directly above the boilers, flinging live coals and splintered timber into the night sky like fireworks. Scalding water and clouds of steam covered the prisoners who lay sleeping near the boilers. Hundreds were killed in the first moments of the tragedy. The upper decks of the Sultana, already sagging under the weight of her passengers, collapsed when the blast ripped through the steamer’s superstructure. Many unfortunate souls, trapped in the resulting wreckage, could only wait for certain death as fire quickly spread throughout the hull. Within twenty minutes of the explosion, the entire superstructure of the Sultana was in flames.’ ” The woman folded the paper and returned it to her pocket.

A man in glasses and a suit said simply, “More people died than on the Titanic.” The others turned to look at him. “History app,” he explained, holding up his cell phone; and he read from the small screen. “Passengers who survived the initial explosion had to risk their lives in the icy spring runoff of the Mississippi or burn with the ship. Many died of drowning or hypothermia. Some survivors were plucked from trees along the Arkansas shore. Bodies of victims continued to be found downriver for months, some as far as Vicksburg. Many bodies were never recovered. The Sultana’s officers, including Captain Mason, were among those who perished.”

“Captain J.C. Mason of St. Louis was a part-owner of the boat,” the woman added. “He should have known better.”

The man in the suit spoke again. “It says here a Sultana survivors group met every year on the anniversary of the tragedy until the last man died on March 4, 1931.”

Appreciative of the man’s contribution, the woman commented that there is still an active Sultana’s descendants’ organization. “This group could maybe contact them.”

The large man in the wrinkled shirt had been quietly reeling inside himself, feeling as if this strange white-haired, and – yes – beautiful woman and her story were affecting his life, beginning with what had been his relatively settled sensibilities before the meeting began. “Are you a member of that group?” he asked her.

Just then the library lights flickered on and off, indicating it was closing time. The Sultana’s story had engaged the impromptu Civil War roundtable group, and now that it was time to go, the woman easily stood up and thanked them for allowing her to join the discussion. Then she simply bid them goodnight. The men sat and stared as she turned and headed towards the stairs.

“Hey, wait a minute,” the heavyset man called, only thinking after the words had left his mouth. The woman stopped and looked back at him. “Um. . . I can walk you out.”

They passed through the library’s automatic sliding main doors and headed for the parking area. The lots were well lit, but the moonless night was dark and all absorbing. The man was wishing they had taken the elevator instead of the stairs, for he was breathing hard and embarrassed by that. He paused to take a deep breath, trying to act if it was a thing he always did.

The woman smiled at him. “I’m just over here,” she said.

“Okay,” the man replied. He fumbled for his keys in his pockets, then in his bag, desperate to maintain her attention. Once found (in one of his rear pockets), he dropped them in the grassy median. “Damn!” he said. “I’m sorry. . . ” he looked sheepishly at her. “I don’t usually curse.” Then, praying for a speedy recovery, he bent over to find the keys. “I’ll be right there.” He was relieved to see a small surface reflected in the parking lot lights, but it turned out to be a damp candy wrapper. He continued to search until he was able to say at last, “Ah, here we go – ”

But when he stood up, the woman was gone. Still breathing heavily, he looked around as far as he could see, but the woman was nowhere to be seen.

– Finis –

____________________________________________________

Some References:

- http://www.riverfrontmurals.com/sultana.htm

- http://www.cityofart.net/bship/sultana.html

- http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2001/05/0501_river5.html

- http://www.historynet.com/sultana-a-tragic-postscript-to-the-civil-war.htm

- http://thesultanadisaster.com/the-sultana-descendants-association/