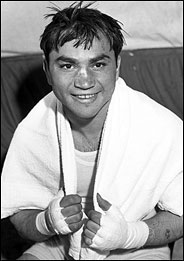

Beryl Rasofsky: 1909 – 1967

By Richard Salzberg © 2013

_________________________________________

“I did a search, like you said, on Barney Ross,” he was saying. “What a story. Really unbelievable stuff. The images that came up were amazing – those classic boxing photos. Man. . . you know, he really was a good-looking guy.”

“Yeah, a good-looking Jewish boy. And tough as nails. . .”

“A real hero. There was just one thing.”

“What’s that?”

“More than half of the pictures that came up were of Sylvester Stallone, or some scary-looking Stallone action figure.”

“Oh, yeah. The ones that looks like Satan on steroids in camo togs and a beret.”

“Well, I don’t care how long ago it was. . . like you said, the real Barney Ross needs to be a household name.”

“He was a household name.”

¶ ¶ ¶ ¶

How many “definites” are there in the life of a great man – or how many absolutes are there in anyone’s life? Despite endless variables and interpretations, key quantifiables can be separated from the lore of any of us. For those who are renowned, when the definites are melded with the lore – then that becomes the legend. Too frequently in our time, however, without benefit of such venerable oral traditions as those of the Basque, the Celts, or the Druse, one generation’s icon and inspiration can become like dust for the generations which follow.

How many “definites” are there in the life of a great man – or how many absolutes are there in anyone’s life? Despite endless variables and interpretations, key quantifiables can be separated from the lore of any of us. For those who are renowned, when the definites are melded with the lore – then that becomes the legend. Too frequently in our time, however, without benefit of such venerable oral traditions as those of the Basque, the Celts, or the Druse, one generation’s icon and inspiration can become like dust for the generations which follow.

All of the above applies to the great Barney Ross.

No matter how condensed, not a word on the subject of Barney Ross could be written today without referencing Douglas Century’s commendable “Barney Ross” (New York: Nextbook/Schocken: 2006).

To try and summarize such a remarkable life which defines some of the most dramatic chapters of the 20th century is a challenge. Born poor – incredibly poor –in New York’s Lower East Side in 1909, Dov-Ber Rasofsky, later Beryl Rasofsky, was the third of six children of Hebrew teacher Itchik Rasofsky and his wife Sarah, new immigrants who had only narrowly escaped the Russian pogroms of the early 1900s. Looking for better opportunities in the west, in 1911 Itchik moved his young family to Chicago before Beryl was two years old, where they settled in the Maxwell Street ghetto. Remembering that the word “ghetto” originated meaning a place specifically for Jews, Maxwell Street is described by Louis Wirth in D. Century’s book as being “full of color, action, shouts, odors, and dirt. . . resembl[ing] a medieval European fair more than the market of a great city today.” Here the Talmudic scholar ran a grocery store “so ramshackle that it had no name;” and so small that no more than three customers could “stand at one time amid the bags of flour and canned goods and pickle barrels.”

Just before Beryl’s fourteenth birthday in December of 1923, Itchik Rasofsky was shot during a robbery and died two days later. After his mother suffered a nervous breakdown and his three youngest siblings were sent to an orphanage, now embittered, the Hebrew school standout and ROTC student ended up quitting school altogether and becoming a determined member of Chicago’s demi-monde. Beryl became a runner for some of Chicago’s notorious Jewish gangsters, and, briefly, for “Scarface” Al Capone, augmenting that work with legitimate jobs, including movie-house usher and stock boy for Sears, Roebuck – committed to nothing but reuniting his grieving family.

Boxing came his way that way. Although a small kid, he was always a tough and clever streetfighter, and now young Beryl was fueled by both anger and ambition. Finding his way to the gritty gyms of Chicago’s boxing world, he was able to channel that toughness and cleverness, combining that with his natural athleticism. He learned his craft the hard way, fight by fight, later being mentored by landsman and welterweight champion Jackie Fields, among others. First in the amateurs and soon in the pro ranks, Beryl gained discipline and experience, garnering attention as he progressed. Boxing provided a perfect outlet for his anger and angst, and, at the age of 19, he began to win steadily – and make money.

The fighting spirit of the ancient Hebrew warriors – Joshua, Gideon, David, the Maccabees, Bar Kochba, and so many others – had generally lain dormant during the years of the Diaspora. But it was always there, circulating in the gene pool and finally bursting forth impressively from the London slums into the fabled bare-knuckle rings of 18th-century England, and later in the early 20th century in the US. The title of Allen Bodner’s 1997 book “When Boxing Was a Jewish Sport,” says it all. Among those countless Jewish fighters and the people they represented, young Beryl Rasofsky became Barney Ross – and Barney Ross became their champion and king of the squared circle.

As quoted in Ken Blady’s excellent book, “The Jewish Boxers’ Hall of Fame” (1988): “I couldn’t hit hard,” Barney admitted, “but I could hit them more than they could hit me. I outmaneuvered them. . . made them fight my fight. I beat the best.”

Interestingly, his father would have forbidden such a career, for it “was drummed into the five Rasofsky boys again and again: a devout Jew should never raise his fists – even in self-defense.” That was for the goyim. It also took some time for his Yiddishe Momme to accept her son as a professional fighter. But eventually Sarah became his biggest supporter; and it was boxing that enabled Beryl to rescue his three younger siblings and provide for his family.

Unless one was there, there is no way to really understand the cultural significance of boxing in the 1920s and 1930s – or the intensity of its ethnic rivalries. After years of perfecting his still-remarkable technique by fighting in small smoke-filled venues in Chicago and all over the country, Ross’ 1933 victory over “the Fargo Express” and future Hall of Famer, Billy Petrolle, led to a series of epic contests with two ring legends: Tony Canzoneri, master boxer and the Lightweight Champion, and later, Jimmy McClarnin, the larger, hard-hitting Irishman and Welterweight Champion. Barney was winner of four of the five fights (controversially losing one of his three with the Irish “Babyfaced Assassin” McClarnin). Only one of these bouts took place in Chicago (the first with Canzoneri), the others were in his opponents’ backyard in New York, Mecca of the sport. Of course, the only way to see a fight in those days was to be there, and several of the celebrated matches between these legendary warriors drew more than 50,000 spectators. Barney emerged from these challenges as the first boxer to ever hold titles in three weight divisions: Lightweight (135 lb.), Light Welterweight (140 lb.), and Welterweight (147 lb.) – and he emerged a wealthy man.

The hundreds of thousands he was to earn were diminished by his renowned generosity, his reputation for being a soft touch, and his poor instincts for investments. Worse – even when he was winning big money in the ring – he had become a slave to gambling. Worse still, Lady Luck scrupulously avoided him. Especially with the horses, Barney was “a bookie’s sweetest dream.”

By the time he faced another ring legend, Henry “Hammerin’ Hank” Armstrong in 1938, Barney had been a professional for almost nine years. Although he was the favorite going in, on May 31 at the Madison Square Garden Bowl in Queens, in the old-timers’ parlance, he suddenly grew old that night. After four competitive rounds, Ross’ renowned movement simply disappeared; he was out-punched, bloodied, and brutalized for the rest of the fight. As well as one of boxing great upset victories by Armstrong, the 15-rounds were also immortalized by Barney’s courage.

He never quit. Refusing to allow his corner to stop the fight through bloody lips (“I’m not quitting. If you stop it, I’ll never talk to you again.”), Barney promised referee Arthur Donovan between rounds that if he let the fight continue, he would afterwards retire. Always a man of his word – that he did. From D. Century: “He had often told sportswriters. . . he would only take one real beating. He wasn’t going to go the route of so many fading champions, gradually diminishing in skill until they are pummeled by third-rate club fighters.”

Barney Ross left the ring with a record of 72-4-3. Incredibly, he was never knocked out or stopped.

Restless and now without purpose at the age of only 29, Barney drifted. A failed marriage and a series of uninspiring jobs, combined with his fabled nightlife contributed to what D. Century describes as “the dark moods.” The country’s entry into World War II after Pearl Harbor resonated, and Barney did not hesitate to answer the call to duty. Although he could have obtained a Coast Guard commission like his friend and former world heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey, or become a boxing instructor like Joe Louis and so many others, in 1942, at the relatively advanced age of nearly 33, Barney enlisted as a private in the US Marine Corps.

Who is not familiar with the name Guadalcanal? (Wait – that is too dangerous a question today.) It was to that tropical atoll in the Solomon Islands that the 145-pound private with gray in his hair was delivered along with thousands of other Marines in November of 1942 – and where Barney Ross became a war hero. Although the details cannot be properly described here, they have been well researched and are well told in Mr. Century’s book, and in Ross’ autobiography, “No Man Stands Alone” (1957).

On November 19, Barney volunteered for a small reconnaissance patrol which encountered a much larger Japanese force. As well as saving the lives of all but two of his seven comrades, and although shot through with bullets and shrapnel, Ross single-handedly stalled a Japanese attack until reinforcements arrived the next day.

During that hellish night in the steaming darkness of the jungle, Barney fired all of his ammunition, then all of that of the men too wounded to use their weapons. He then began throwing grenades – all that they had – wherever he heard a sound. He later told his younger brother George that, during all the pain and fear and delirium – and the desperate prayers – he saw a gaunt, bearded man in an old white grocer’s apron. “You have no idea how I talked to Pa throughout that night,” he said.

For this heroism on that small, then-priceless place the middle of the Pacific – Pvt. Barney Ross was awarded the Silver Star and promoted to Corporal. He recovered well enough to return to the frontlines on “the Canal” five more times, but he continued to suffer terrible bouts of malaria and from the severe wounds that troubled him for the rest of his life. It is said that some of his comrades became overly solicitous while he was still on the island, providing too much of what he needed for relief, and later, while he was recuperating in New Zealand, and after he returned to the states as well.

In short: He was introduced to morphine. It was the only thing that could ease the searing pain that consumed him, and subdue the malarial shakes that wracked his body. Despite the hero’s welcome and his standard-bearer status for all things patriotic and American. . . the great Barney Ross had become a drug addict.

After years of living the wraith-like, duplicitous existence of a junkie, in late 1946, Barney had himself committed to the U.S. Public Health Service Hospital in Lexington, Kentucky, to be treated for heroin addiction. The “reduction method” developed there was known as an addict’s last chance; and, as described in William Burroughs’ 1952 book, “Junkie” – it was brutal. After more than four painful months, Barney emerged from the gray walls of the “fortresslike complex,” eventually to be considered cured. He described the experience as the most difficult fight of his life.

Interestingly, D. Century writes: “He credited the Jewish faith learned at his father’s knee with helping him beat addiction.” When Ross later provided an account of the excruciating struggle for Coronet magazine it was entitled “God Was in My Corner.”

Admiration and accolades for the man never ceased, nor did the good deeds he quietly performed for others down on their luck. His jobs were sporadic, the ongoing gigs expected of a celebrity, radio and television appearances, some front-man work, and a labor relations manager for a shipbuilding company. He did some refereeing and helped manage a few young fighters, and he became a sort of glorified bodyguard to Eddie Fisher and Elizabeth Taylor. He even played himself in Rod Serling’s classic “Requiem For A Heavyweight.”

Barney Ross never lost the character of a champion. And, be it as an elder statesman for boxing or a forthright advocate for drug addiction awareness – he never lost his identity or pride as a Jew. In the late 1940s he was said to be involved in acquiring arms for the fledgling state of Israel during its War of Independence; and he was central in efforts to create an Abraham Lincoln Brigade-like organization to be composed of Jewish veterans and others – the George Washington Legion – to help Israel defend itself against its Arab enemies. That plan was quashed by the virulently anti-Israel State Department, but Barney never stopped lobbying for the young Jewish state.

Death caught up with Barney Ross far too early. Only 57 years old, in mid-1966, he fell ill. He became very sick, and there were large medical bills. That led to fund-raisers and tributes, with the boxing community and others responding the way Barney had always treated his many friends: with generosity and unwavering loyalty. Even though Barney was too ill to be there, the tributes brought out the old champions and former contenders, and current champs and young contenders. There were celebrities, and young Marines from Viet Nam with Purple Hearts, and the older journalists who had covered the “the tough Jewish kid from Chicago” during his many glory days, and they sang his praises and watched the old fight films. They all came out for Barney Ross.

His older brother Ben issued a statement in late December: “The family now feels that all of Barney’s needs have been met and that his friends have contributed enough.” Barney Ross died on Jan. 18, 1967, at home in Chicago.

He played a conspicuous part in the history and culture of his times that should never be forgotten: The mean streets of Chicago and the Maxwell Street ghetto, the Great Depression, the worlds of boxing and professional sports, the Marine Corps and some of the worst fighting of World War II, and the tumultuous post-war period – Barney Ross was there.

Rest in peace, Dov-Ber Rasofsky. God knows, you earned it.

– Finis –

___________________________________________________