About Mr. Lincoln’s Movie(s)

By Richard Salzberg © 2012

_________________________

As far back as “The Birth of a Nation” in 1915, no less than 20 actors have portrayed Abraham Lincoln on the big screen. Notables having essayed our 16th president in film include John Carradine; Walter Huston; Henry Fonda; Raymond Massey; John Anderson; Jason Robards; Hal Holbrook; and most recently, Daniel Day-Lewis in Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln.”

Some actors played Lincoln more than once, including Massey, Anderson, and Frank McGlynn, Sr. (who had the role in three different films in the 1930s); and, in the mysterious way of the serious actor’s work, it is assurable that all who interpreted the legendary figure had at least a partial first-hand glimpse into the spirit of the great man.

However it is Carl Sandburg (1878–1967), poet, musician, folklorist, and three-time recipient of the Pulitzer Prize – and the foremost Lincoln biographer – who clearly, among all of those who never met the man, understood him best.

Through an intermediary in December of 1940, Hollywood producer Walter Wanger expressed an interest in Sandburg helping with a bio-pic on explorer John C. Frémont, “the Great Pathfinder,” and Union general. Considered to be “among the more literate and socially conscious American film producers of his time,” Wanger (1894–1968), had a career spanning decades, beginning with the Marx Brothers’ “Cocoanuts” in 1929, and ending with Elizabeth Taylor’s “Cleopatra” (1963).

Carl Sandburg, 1938

Although that collaboration never occurred, in a letter to Wanger dated December 14, 1940, Sandburg wrote: “One reason I am willing to work on a Fremont picture, aside from its personal appeal, is that during the time we worked on it, we could talk over the field of a Lincoln picture. I think I know why the (Ray) Rockett film, the Griffith, the Sherwood-Massey failed to go over. It might be that I could lay before you a number of Lincoln scenes that would have their point for the crises that lie ahead the next few years. We would have no understanding at all that there is to be a Lincoln picture. Yet it might be that with a few long discussions, covering a thousand possible angles, we would arrive at a Lincoln story that would become a classic. My own approach to a Lincoln book has always been slow and tentative. Perhaps I mean that you and I could make some reconnaissance flights – afterward deciding whether to attack.”

So here we have the great Carl Sandburg pitching his concept for a dream film on Lincoln just like a kid fresh out of NYU Film School; and – with all of Sandburg’s inspired knowledge of the subject – how utterly tantalizing it is to consider what that movie would have been.

The beginnings of many fine films begin with dramatic beginnings. Thanks to The Lincoln Society of Virginia [www.lincolnva.org] and its commendable purpose, there are a number of stirring and unexpected possibilities. Those include:

● With his paternal ancestors originally from Hingham, England, Abraham Lincoln’s great-grandparents and his grandfather – for whom he was named – were early pioneers of Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, having migrated from Massachusetts, via New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Abraham Lincoln – President Lincoln’s grandfather and namesake – married Bathsheba Herring, a native of Rockingham County, Virginia.

● “During the American Revolutionary War, Abraham (the grandfather) served as a captain of the Augusta County militia, and with the organization of Rockingham County in 1778, he served as a captain for that county. He was in command of sixty of his neighbors, ready to be called out by the governor of Virginia and marched where needed. Captain Lincoln’s company served under General Lachlan McIntosh in the fall and winter of 1778, assisting in the construction of Fort McIntosh in Pennsylvania and Fort Laurens in Ohio.”

● “In 1780, Abraham Lincoln sold his land on Linville Creek, and in 1781 he moved his family to Kentucky, then a district of the Commonwealth of Virginia. The family settled in Jefferson Count, about twenty miles (32 km) east of the site of Louieville. The territory was still contested by Indians living across the Ohio River. For protection the settlers lived near frontier forts, called stations, to which they retreated when the alarm was given. Abraham Lincoln settled near Hughes’s Station on Floyd’s Fork and began clearing land, planting corn, and building a cabin.”

● “All of their children – including Tom Lincoln (1778–1851), the father of Abraham Lincoln – were born in Rockingham County. Although Tom moved with his family to Kentucky (where the future president was born), several of Lincoln’s cousins remained and some still live in the area. Five generations of Lincolns are buried in the family cemetery.”

If nothing else would be used. . .

● “One day in May 1786, Abraham Lincoln was working in his field with his three sons when he was shot from the nearby forest and fell to the ground. The eldest boy, Mordecai, ran to the cabin where a loaded gun was kept, while the middle son, Josiah, ran to Hughes’s Station for help. Thomas, the youngest, stood in shock by his father. From the cabin, Mordecai observed an Indian come out of the forest and stop by his father’s body. The Indian reached for Thomas, either to kill him or to carry him off. Mordecai took careful aim and shot the Indian in the chest, killing him.” Tom Lincoln was understandably forever changed by this tragedy, and his second child, first son, and the 16th president, was so named Abraham.

As for the contemporary Lincoln movie experience. . .

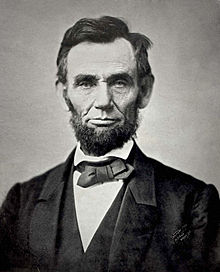

Lincoln by Gardner, 1863

Inasmuch as nothing can now be done to advance Carl Sandburg’s cinematic vision for Abraham Lincoln (beyond possibly joining him in the realms of our imaginations), all we can do is await the interpretation of Lincoln and his life as crafted by Messrs. Day-Lewis and Spielberg, two of the most talented and successful practitioners in the history of their professions. Will the 2012 Lincoln be colored and directed to some degree by contemporary sensibilities and hindsight? The answer is easy: Yes.

But that “we the people” are currently perceived by Hollywood moguls and business people as still having enough intelligence to find the history of Abraham Lincoln compelling enough to be allowed another film on the subject is in itself a positive sign. To formularize: Race Memory + Cultural Commerce = Hope.

– Finis –